As a registered nurse, I sometimes work with patients that have been diagnosed with a terminal illness. One of the most common questions from them is also one that takes a fair amount of courage for them to ask out loud: How long?

It is also one of the most difficult to answer. How long depends on a lot of things. Some patients outlive their prognosis considerably, others may pass long before the estimated time. It's often a guessing game. All we know is that there will be an end, and that it won't be long.

Unlike most medical treatments, in palliative care the focus is not on curing the disease. Rather, we focus on symptom management until the end. Comfort care we call it. All medical treatments focus on providing comfort for the patient rather than removing the actual causes of affliction.

In a sense, we all are terminal. There is no cure for mortality, except through death and the promise of an eventual resurrection. We all have been designated as "comfort care measures only." There are some spiritual diseases that can be cured, certainly. Repentance does wonders, for one thing. But generally speaking, we are here to experience for ourselves spiritual and physical death. Spiritually, we are in a fallen world that has limitations on what we can do, and we face mortal challenges that cause us pain, suffering, and sorrows. If we are in tune to this reality at all, we might, in anguish of spirit, ask our Lord and Physician, "How long?"

How long must we suffer? How much time do we have? How long until this is all over?

This is usually asked when circumstances are such that we are forced to face our diagnosis in some way because we are in great pain. We might spend a lot of time and energy not facing our mortality and sins, of course, avoiding our spiritual disease until at last something happens and we have to confront it in ourselves. Trials come to all of us, and sometimes the symptoms of the disease of mortality can be pretty severe.

The question, "How long" is very scriptural. It is a normal, even necessary step. The lament is a part of our journey towards our Physician, the Savior Jesus Christ. When we ask that question we are in good company.

For example, when Joseph Smith was in Liberty Jail in perhaps the lowest point in his life, he asked the Lord that question. "O God, where art thou?...How long shall thy hand be stayed, and thine eye, yea thy pure eye, behold from the eternal heavens the wrongs of thy people and of thy servants, and thine ear be penetrated with their cries?" (D&C 121:1-2)

Alma asked that same question "How long shall we suffer these great afflictions, O Lord?" (Alma 14:26) after seeing the people he converted thrown into a fire and was himself imprisoned and suffered great cruelty at the hands of his oppressors.

Job asks his unhelpful friends, "How long will ye vex my soul and break me in pieces with words?"

Habakkuk asks, "O Lord! How long shall I cry and thou wilt not hear!"

Numerous prophets were very familiar with the lament of How long?

Out of all scripture, however, it is the Psalms that use the phrase How long? the most.

Traditionally, we know the Psalms are hymns of praise, but we sometimes forget that they are also hymns of lamentation. The Psalms blur the line between lamenting and praising God. In fact, the two opposing ideas can actually happen in the same prayer. Can we really learn to lament the reality of our circumstances and praise God at the same time?

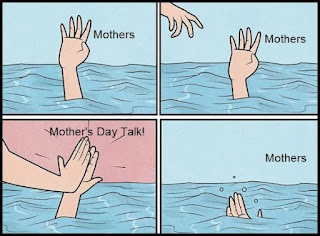

We live in a culture that eschews the lament. "Don't be so dramatic," we say to the person who is in process of rending their garments and covering themselves with sackcloth and ashes. "Don't you know things will be alright?" "If you just had more faith, you could see the hand of the Lord in your life." We conceal suffering, teaching our primary children: "No one likes a frowny face. Change it for a smile!" "Scatter sunshine all along the way!" We call honest, soulful anguish the "ugly cry." The lament is pushed away in our interactions with each other. We hide our deepest sorrows, our most painful wounds, from each other.

Sometimes, the lament needs to come first before we can rejoin the ward choir praising God. In my experience, a stifled lament will always get in the way of our journey to Christ. I am convinced that faking joy will eventually make our worship hollow. God does not want us to pretend away our suffering. That will deaden us spiritually as much as anything.

Christ, our perfect example, taught us how to truly lament: "My God, my God, why has thou forsaken me?" In Gethsemane, in the act of atonement, Christ did not kneel down to praise His Father. He knelt down and lamented to Him.

Telling someone in their own personal Gethsemane to praise God instead of allowing them to lament goes against Christ's example and, unless we allow a friend or family member the appropriate time to lament, could become spiritually toxic. Continuing to hide our sorrows will divide us from each other instead of knit our hearts together in love.

As much as I wish we could, we cannot skip the lament on our path of discipleship. We cannot praise God without first recognizing and acknowledging the sorrow, the pain, the anxiety, and the human weakness that He delivers us from. He does this in His time, not ours.

That does not mean we turn away from Christ in our sorrows. On the contrary, looking to Christ in our suffering is the very essence of the lament. We turn to Him when there is no one else to turn to. It is a part of looking to His suffering and beholding His wounds, weaving our narrative of suffering with His. Remember the Nephites lamenting because of the loss of their loved ones in the destruction in fires, earthquakes, etc. When Christ came down, He first asked them to behold His wounds. We can behold His suffering even before He heals us of our own wounds, because His wounds are our wounds. Having faith in Christ means connecting our suffering to His.

Do latter-day saints know how to lament?

I have a six year old daughter who is an expert at lamenting. It is not a skill I have. To my detriment, I am more of an expert at concealing and discounting negative feelings, but I have learned this is not helpful when someone is truly sorrowing. If I come in armed with explanations and resolutions and sunshine to shine on her problems while she is still lamenting, I make the problem worse. The howls get louder because obviously I can't see her suffering. I have learned that I need to get down in the sorrow with her, even if I think things will be alright. I have to mourn with her. I have to support her in her lament, to validate the six year old sorrow she is feeling. The lament is a part of healing, and trying to taking it away from her does more damage than good.

In my limited experience, more often than not I see us hiding the lament from each other. We skip that part. We bear our testimonies about how Christ is with us in the resolution of our problems. That part is obvious. But it is harder to bear our testimonies that Christ is with us while we are still in the thick of it, when He is silent, when He seems invisible to us, when it feels like we have to trudge our path alone, and we are mired in the mud. (Psalm 69)

Perhaps we fear that if we are not feeling peace and joy in the gospel, we are doing it wrong. Or that we are somehow unworthy of the blessings. Sometimes we feel alone because there must be something wrong with us if we feel this way, especially when we feel like we are the only one who isn't having a nice time at church. When everyone else is wearing their Sunday best faces, how can we show up at church with a face full of sackcloth and ashes? Or worse, maybe we fear the the Lord has really abandoned us after all.

Is our suffering even welcome at church?

Each of us made a covenant at baptism that we would mourn with those that mourn, and comfort those who stand in need of comfort. We made a covenant to share each other's burdens. (Mosiah 18)

Can we do this when we consistently hide our burdens from each other?

Perhaps our culture could use an adjustment. In my opinion, I think we need to learn better how to mourn with those that mourn. "Blessed are those that mourn." We need to restore the lament as a vital, holy part of our worship. "How long," should not be seen as a lack of faith, but as a sacred prayer.

Sister Amy Wright in this last General Conference states:

"Oftentimes we can find ourselves, like the lame beggar at the gate of the temple, patiently—or sometimes impatiently—“wait[ing] upon the Lord.” Waiting to be healed physically or emotionally. Waiting for answers that penetrate the deepest part of our hearts. Waiting for a miracle.

"Waiting upon the Lord can be a sacred place—a place of polishing and refining where we can come to know the Savior in a deeply personal way. Waiting upon the Lord may also be a place where we find ourselves asking, “O God, where art thou?”—a place where spiritual perseverance requires us to exercise faith in Christ by intentionally choosing Him again and again and again. I know this place, and I understand this type of waiting."

"Waiting upon the Lord can be a sacred place."

Some of my most sacred prayers I have offered in my life have been angry prayers. Prayers that came from a place of intense suffering. Those hot angry tears when the heavens felt like brass and when the suffering continued in spite of my best attempts to live the gospel—when I felt forsaken and downtrodden and forgotten and left in extreme anguish of spirit. Looking back, it was in those moments that I have connected with Christ the most, when I have tasted in some small way the bitter cup of Gethsemane and known that He understands what it is like to suffer. He suffered so that "he may know how to succor his people in their infirmities." (Alma 7) Like Paul, my allotted suffering has become holy to me because it was in it that I understood better what my Savior suffered for me.

When we sing, "Who, who can understand?" we find the answer: "He only One." (Hymn 29 Where Can I Turn for Peace) Christ's words to the lament of Joseph Smith in Liberty Jail was this: "The Son of Man hath descended below them all. Art thou greater than thee?" (D&C 122:8) Our physician is the only one who knows how to provide "comfort care" in our long, slow, painful palliation. But He is with us to the end.

If you are lamenting, let yourself. Lament to the Lord. Connect your suffering to His. Without any resolution on your horizon, still mired in the mud and sinking, waiting for the miracle that doesn't seem to arrive, when all your faith feels vain, let yourself lament. Cry unto the Lord. "How long!" This is a sacred prayer. Your lament is a vital part of faith in Christ. You are in a sacred space. You are connecting yourself to Him in a way that is every bit as meaningful as any prayer of praise because you are connecting directly to Christ's atonement. He is a man despised, rejected, and acquainted with grief. (Isaiah 53) This is your path to become like Him, and you do not have to walk it alone because you are never closer to Christ than when you are walking the lonely path He trod.